Feedback can be defined as a special form of communication. Just as the term communication is used generally to mean a message, the term feedback can designate a specific type of message. The question then is what distinguishes feedback from other forms of communication. Beyond those dimensions that all messages must contain to be deemed communication, what are the characteristics that allow us to categorize this or that message as feedback?

A message doesn’t exist on its own, however. Among other things, it needs a sender and a receiver. Furthermore, a message occurs within a certain context or environment. For these reasons, I want to start by looking at the larger landscape of the communication process.

Below are three basic models from the countless number of communication models developed over the last fifty-plus years. Each of the three provides an increasingly complex view of communication as an interpersonal exchange. By examining the general process of communication, we can also begin to understand the feedback process which will inform a later discussion of the characteristics of feedback messages.

Finally, to take this one step further, we’ll look at a graphic that illustrates the complex, work-related systems in which feedback functions. Three core assumptions underlay this model. Firstly, feedback arises from sources other than the manager. Secondly, feedback occurs outside the formal feedback systems. Finally, feedback as a message and as a process will be shaped/influenced by these various systems in ways that will not always be apparent.

KEEP IN MIND: A model is a great tool. It can help one imagine a difficult-to-envision phenomenon. A model provides an organized view of relationships between key elements and generates insight into a phenomenon’s operation. At the same time, it’s important to remember that a model is a “consciously simplified description in graphic form of a piece of reality.”(1) A model represents a point of view on the phenomenon being represented. Model makers omit elements based on assumptions. Sometimes the assumptions are known; sometimes they are hidden, even to the model maker. Additionally, we make assumptions when viewing a model. So, as you look at these models, don’t forget to ask what is missing and why. What were the assumptions of the model maker and how is the model influencing me?

(1) Mc Quail, D., & Windahl, S. (1993). Communication models for the study of mass communications (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

LINEAR/INFORMATIONAL COMMUNICATION MODEL

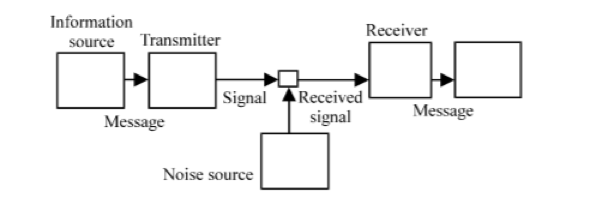

C. E. Shannon outlined this communication model in 1948 while working as a mathematician at Bell Labs.

Known as the Shannon-Weaver model, this source-receiver diagram focuses on signal processing that does not add or subtract content. This visual is in support of mathematical processes to reduce or eliminate noise that affects data moving through communication channels. Channels (means of transmitting/receiving) in this model would refer to a phone or computer transmission line. Noise (that which interferes with clean transmission/reception) might include poor-quality wire or a failing relay.

This model has been, and continues to be, applied to human communication in the basic sender-message-receiver diagram that everyone is familiar with. While generally informative, there are some gaps when examining interpersonal exchanges. For example, in this model, a message is successfully communicated if the received words and their order are identical to those sent. Communication is reduced to a mirroring process. Limiting the message in this way does not address multiple meanings that often arise in such situations as feedback. A second example is the linear nature of the flow in this representation. It seems to say that communication is a straightforward, cause-and-effect process. Anyone who has given or received corrective feedback knows communication processes can be decidedly unpredictable, operating in non-linear ways.

If feedback operated as the Shannon-Weaver model suggests, it might be called “Tell and Sell”(2). This feedback process would be an effort in persuasion. The manager tells the subordinate what must change and then follows with motivational efforts to overcome any objections raised by the receiver. To stretch the analogy, the objections are the result of noise in the system. By restating the original message and providing an argument for why the employee needs to make the change, the manager attempts to reduce the noise. When the subordinate agrees to the message (i.e., mirrors it), agreement is confirmed by the development of a plan to achieve changes. While there are likely circumstances in which this approach would work, communication is not restricted to this narrow vision of feedback.

(2) Maier, N. R. F. (1976). The Appraisal Interview: Three Basic Approaches. San Diego: University Associates, Inc.

CIRCULAR/INTERACTIONAL COMMUNICATION MODEL

Various later theorists have adapted or reimagined the Shannon-Weaver model. One example is the Osgood and Schramm’s (1956, originated by Osgood and cited by Schramm in 1954) circular model. Here communication is depicted as two-way and ongoing. A message-sender encodes a message which the receiver decodes and interprets. The receiver then encodes a feedback response, and so on as the cycle repeats.

Two-way, interactional models like this acknowledge that the message is more than the mirroring of transmitted words and sentence structure. There must be listening and feedback. The downside in these models is that they assume a sort of stimulus-response pattern of communication. Although communication is represented as having a back-and-forth quality, there is still just one message-sender and the feedback is just a patterned form of feedback that ultimately makes this closer to a linear model.

A feedback model in this vein might be called “Tell and Listen.”(3) Here the manager would provide the feedback and then actively listen to concerns and feelings. The manager explores without judgment or counterargument. The goal is more one of catharsis for the employee and it may provide insight for the manager. However, there is no fundamental change to the feedback because the message is presumed accurate, complete, and necessary. Again, there will be feedback situations where this will be a viable approach.

(3) Maier, N. R. F. (1976). The Appraisal Interview: Three Basic Approaches. San Diego: University Associates, Inc.

TRANSACTIONAL/SIMULTANEOUS COMMUNICATION MODEL

Concurrent with some of the two-way models have been efforts to address the idea that people come into an interpersonal exchange with different points of reference. In these models the exchange is a dialogue with both participants acting as senders and receivers. Participants engage in simultaneous message exchange that, when coupled with productive feedback (active listening for clarification, reiteration, etc.), hold the promise of co-creating a shared understanding.

This model (adapted from Adler & Town, 2010; Berlo, 1960; Schramm, 1956) recognizes each person’s unique mix of skill and experience that influences how each understands the meaning of words, develops and delivers messages and gives and responds to feedback. It presents participants as both senders and receivers of messages and feedback. It also includes the various environmental factors that may influence the communication process.

COMPLEX SYSTEM FEEDBACK MODEL

The communication models reviewed so far look at communication (and thus feedback) as an exchange between people. They don’t address the impact of feedback from other sources including nonhuman sources. They don’t consider the influence of these other sources on the feedback content and process.

We tend to study feedback up close; that is, at the level of the manager and subordinate exchange. If feedback fails (or succeeds), we tend to look to actions by the manager or subordinate to explain what happened. While these individuals usually play a key role, the feedback process does not function in isolation.

Feedback processes operate within the broader complex of an organization’s internal systems and intersecting external systems. To understand feedback failure (success) it is useful to consider these other elements. Examining these complex systems and their potential impact provides insight into the nonlinear nature of feedback, insights that may prove useful in future feedback exchanges.

Feedback arises from a wide range of sources. The obvious sources are in the form of interpersonal communication from a boss, co-worker, or professional colleague. One can also get feedback from customers or clients or some other entity like a government agency or a competitor. Feedback, in some cases, can be generated from the work itself, as in a manufacturing setting when a product comes off the line. We can also give feedback to ourselves when, e.g., we notice an error. The organization may provide direct feedback in the form of a promotion or salary increase, or indirectly through organizational values that promote certain work or professions over others.

Systems also shape how feedback is developed and deployed. An organization with a highly engineered peformance management system might have extensive performance information along with a complex set of procedures for the dissemination of it. In a blue chip, global organization with a long history, traditional practices and ingrained values will influence the content of feedback and how one is expected to receive and act on it. Organizations with strict hierarchies provide another example of how systems can shape and influence the feedback process.